Book summary: The Culture Code by Daniel Coyle

Here’s my review of The Culture Code by Daniel Coyle. (Originally recapped and published to my email newsletter group July 2020. All of the ideas except those noted in the footnotes are Daniel’s either in his own words or paraphrased.)

I love this book for its tips on creating high-purpose teams and highly productivity environments in which they can thrive. One of the biggest epiphanies for me in the last decade is found in this book – how trust is built. See the Vulnerability Loop graphic below.

What I liked most about this book is that all of the suggestions offered for building a stronger culture were research-based. While I have not referenced the research in this summary, you can refer to the book to find the actual studies.

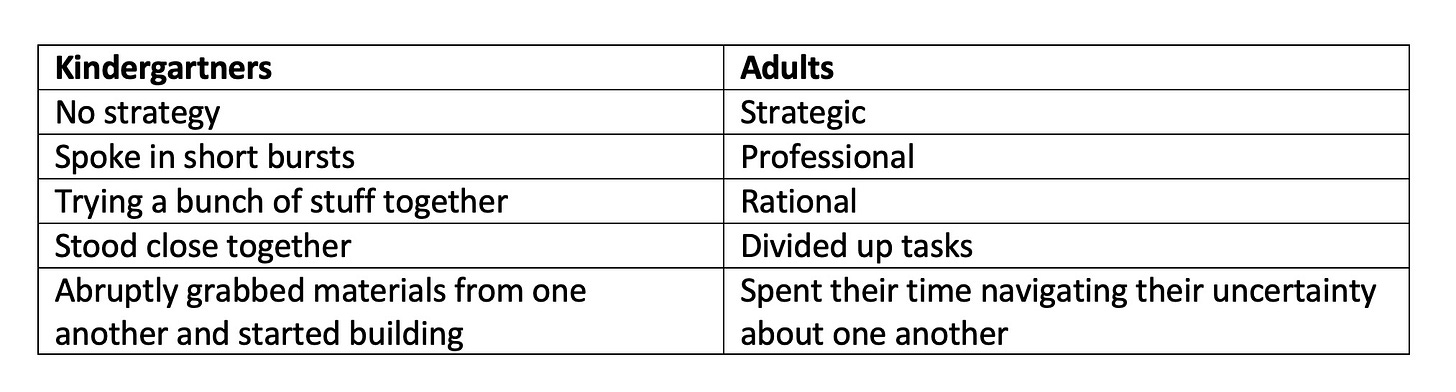

The beginning of this book starts out by describing how and why kindergarteners were able to best adults in a contest to build the tallest tower from marshmallows and sticks.

Kindergartners versus adult

The kindergartners won because they were not competing for status, they worked energetically and in close proximity to each other, they moved quickly and spotted problems and offered to help each other. They experimented, took risks, noticed outcomes and moved toward effective solutions.

This is what effective culture looks like.

Cultures are created by a specific set of 3 skills

Build safety

Share vulnerability

Establish purpose

1. Build safety

Safety is not mere emotional weather but rather the foundation on which strong culture is built. Actions of tight knit groups:

Close physical proximity, often in circles

Profuse amounts of eye contact

Physical touch (handshakes, fist bumps, hugs)

Lots of short, energetic exchanges (no long speeches)

High levels of mixing; everyone talks to everyone

Few interruptions

Lots of questions

Intensive, active listening

Humor, laughter

Small, attentive courtesies (thank you, opening doors)

The ever-present question in our brains is: Are we safe here in this group? What’s our future with these people? Are there dangers lurking?

Our unconscious brains are obsessive about answering these questions all the time. We require a lot of ongoing signaling to confidently answer these questions. That’s why a sense of belonging is easy to destroy and hard to build. Make sure every signal you send is a signal of belonging. Do that by making sure it has energy (I’m intentionally being here with you. We are close), individualization (You are unique and valued. Who you are is safe with me.) and future orientation (Our relationship will continue. We share a future.).

Team performance is driven by five measurable culture factors

Everyone in the group talks and listens in roughly equal measure, keeping contributions short.

Members maintain high levels of eye contact, and their conversations and gestures are energetic.

Members communicate directly with one another, not just with the team leader.

Members carry on back-channel or side conversations within the team.

Members periodically break, go exploring outside the team and bring information back to share with others.

“I’m so sorry about the rain. Can I borrow your cell phone?”

Adding “I’m sorry” about a shared experience before asking for a request made a difference in the response rate of people who said yes.

One misconception about highly successful cultures is that they are happy, lighthearted places. This is mostly not the case. They are energized and engaged, but at their core their members are oriented less around achieving happiness than around solving hard problems together. This involves many moments of high-candor feedback, uncomfortable truth-telling. They confront the gap of where the group is and where it ought to be. “Tell the truth with no bull shit, and then love to death afterward.”1

One particular format of giving feedback will boost effort and performance. Research has proven it’s almost “magical” in its effect. It consists of this one simple phrase:

“I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations, and I know that you can reach them.”

Proximity functions as a kind of connective drug. Get close, and our tendency to connect lights up. Closeness helps create efficiencies of connection.

Ideas for action – Creating safety is about dialing into small, subtle moments and delivering targeted signals at key points.

Be still and lean in when someone is speaking. Look at the speaker’s eyes and listen intently. Provide a steady stream of affirmations – such as yes, uh-huh, gotcha. Avoid interruptions.

We have a natural tendency to try to hide our weaknesses and appear competent. If you want to create safety, this is exactly the wrong move. Open up, show you make mistakes and invite input. Use phrases like “This is just my two cents.” “What am I missing?” “What do you think?” Actively solicit input. Leaders should be asking everyone: What do you like most about our group? What do you like least? What would you change if you were in charge?

Leaders should do the menial work. Seek simple ways to serve others.2

Overdo it on thank you. It has less to do with thanks than affirming the relationship. They aren’t only expressions of gratitude; they’re crucial belonging cues that generate a contagious sense of safety, connection and motivation.

Maintain an extremely low tolerance for bad-apple behavior that destroys safety.

Create spaces and opportunities for people to collide. Design experiences so that they put people in close proximity to each other to have conversations and encounters.

Pay attention to ‘threshold moments’ – Successful groups pay attention to moments of arrival. They pause, take time and acknowledge the presence of the new person, marking the moment special.

Avoid sandwich feedback (positive-negative-positive). Instead separate feedback by type. For negative feedback, first ask if the person wants feedback. If they are open to it have a two-way conversation about needed growth. For positive feedback, provide it in ultra-clear, spontaneous bursts. Radiate delight when you spot behavior worth praising.

Embrace fun. Laughter is the most fundamental sign of safety and connection.

2. Share vulnerability

When you watch highly cohesive groups in action, you will see many moments of fluid, trusting cooperation. Sprinkled amid the smoothness and fluency are moments that don’t feel so beautiful. These moments are clunky, awkward and full of hard questions. They contain pulses of profound tension, as people deal with hard feedback and struggle together to figure out what is going on. What’s more, these moments don’t happen by accident. They happen by design.

This chapter introduces the concept of the vulnerability loop – the most basic building block of cooperation and trust.

“People tend to think of vulnerability in a touchy-feely way, but that’s not what’s happening. It’s about sending a really clear signal that you have weaknesses, that you could use help. And if that behavior becomes a model for others, then you can set insecurities aside and get to work, start to trust each other and help each other. If you never have that vulnerable moment, on the other hand, then people will try to cover up their weaknesses, and every little micro task becomes a place where insecurities manifest themselves.” 3

Vulnerability doesn’t come after trust – it precedes it. Leaping into the unknown, when done alongside others, causes the solid ground of trust to materialize beneath our feet. Exchanges of vulnerability, which we naturally tend to avoid, are the pathway through which trusting cooperation is built.

Design experiences where the team is in close proximity and can experience each other’s vulnerability. An example is the Navy Seals and their log physical training (carrying a log together over long distances). These are where vulnerability meet interconnection and deep trust is built.4

One of the principles discussed in this section of the book is after-action reviews. The purpose of an after-action review is to build a shared mental model that can be applied to future shared situations. The goal of an after-action should be to see the truth and take ownership.5 The real courage required in an after-action is to see the truth and speak the truth to each other. Always be asking: What’s really going on here?

Ideas for action – Building habits of group vulnerability is like building a muscle. It takes time, repetition and the willingness to feel pain in order to achieve gains.

Make sure the leader is vulnerable first. These might be the most important four words any leader can say: “I screwed that up.”

Leaders should consider asking:

What is one thing that I currently do that you’d like me to continue to do?

What is one thing that I don’t currently do frequently enough that you think I should do more often?

What can I do to make you more effective?

Overcommunicate expectations. Send big, clear signals that establish expectations, model cooperation and align roles to maximize helping behavior.

When forming a new group, focus on two critical moments: The first vulnerability moment. The first disagreement.

Creating vulnerability often resides not in what you say but in what you do not say. This means having the will power to forgo easy opportunities to offer solutions and make suggestions. Don’t offer suggestions as a substitute for active listening. Suggestions aren’t reciprocation. And they should be invited before being offered. Instead, keep the other person talking: “Say more about that please.”

When giving feedback, aim for candor and avoid brutal honesty. Candor involves feedback that is smaller, more targeted, less personal, less judgmental and equally impactful.

Recognize that creating habits of vulnerability will require a group to endure two discomforts – emotional pain (shouldn’t we be patting ourselves on the back and not asking what went wrong or we could have done better?) and a sense of inefficiency (shouldn’t we be moving forward instead of looking backward?).

3. Establish purpose

When successful groups communicate their purpose, they are subtle as a punch in the nose.

They focus their language on catchphrases and mottos. They fill their surroundings with reminders of this purpose. Purpose isn’t about tapping into some mythical internal drive but rather about creating simple beacons that focus attention and engagement on shared goals.

Successful cultures do this by relentlessly seeking ways to tell and retell their story. They find small, vivid signals designed to create a link between the present moment and the future ideal. Here is where we are and Here is where we want to go.

Successful cultures use mental contrasting: Envision a reachable goal and then envision the obstacles to get there.

Stories can help describe goals and the future we envision. Stories are the best invention ever created for delivering mental models that drive behavior.[1]

Establishing purpose is different based on whether the desired outcome is consistency or innovation.

If the goal is consistency, then the high-purpose environment needs to send a handful of steady, ultra-clear signals that are aligned with a shared goal, not so much one big signal. Create a simple set of rules that stimulate complex and intricate behaviors benefitting customers. If this … then that. These catchphrases then become heuristics that provide guidance by creating vivid and memorable if/then scenarios.

If the goal is innovation and creativity, use processes and structure to help create the safety needed to guide the group to new ideas. Generating creative purpose is like supplying an expedition: You need to provide support, fuel and tools and to serve as a protective presence that empowers the team doing the work.

Ideas for action

“Building purpose is not as simple as carving a mission statement in granite or encouraging everyone to cite from a hymnal of catchphrases. It’s a never-ending process of trying, failing, reflecting and above all learning. High-purpose environments don’t descend from on high; they are dug out of the ground, over and over, as a group navigates its problems together and evolves to meet the challenges of a fast-changing world.”

Name and rank your team’s priorities. You should have five of fewer. Often, how group members treat each other will be one of the Top 5 priorities.

Be 10X clearer about your priorities than you think you should be. Everyone should be able to name your priorities from memory.

Embrace the use of catchphrases. Engage your team in creating sticky ones that are memorable.

Celebrate when team members exhibit one of your catchphrases in action.

In a latter-day saint context this could also be said using Doctrine & Covenants 121:43: “Reproving betimes with sharpness, when moved upon by the Holy Ghost; and then showing forth afterwards an increase of love toward him whom thou hast reproved, lest he esteem thee to be his enemy.”

Matt 20:27 – “He who would be chief among you, let him be your servant.”

Christlike service to one another becomes our opportunity to go through the vulnerability loop. Someone admits or invites others to help (Stage 1), others detect the sincerity of the request (Stage 2) and we match or reciprocate by showing up to help (Stage 3). Mosiah 18:8-9: “And it came to pass that he said unto them … now, as ye are desirous to come into the fold of God, and to be called his people, and are willing to bear one another’s burdens, that they may be light; Yea, and are willing to mourn with those that mourn; yea, and comfort those that stand in need of comfort, and to stand as witnesses of God at all times and in all things, and in all places that ye may be in, even until death, that ye may be redeemed of God, and be numbered with those of the first resurrection, that ye may have eternal life.”

On dairies, this could look like pulling milking inflators together or helping to cover a silage pile with tires. The Amish have it figured out with barn-raising events. I’ve best experienced this in my own congregation wood-cutting and wood-stacking service projects. At Progressive Publishing where I work, these opportunities come when someone moves in and we help them unload the moving truck or with our human chain of people to load Christmas candy packages into the mail truck (although this admittedly isn’t a very strenuous task). We did have one activity as a group to paint Joseph’s Closet that created this closeness.

Example: After one production I talked to a member of our team about how production could help us by improving the accuracy of author’s data tables being rebuilt in InDesign. It’s probably not what he wanted to hear, but it was the truth.